In 2017, when New York Times reporter Nikita Stewart heard about a Girl Scout troop meeting in a Queens, New York, homeless shelter, she jumped at the chance to cover it. Little did she know, however, that her story would go viral, changing not only the lives of the girls in Troop 6000, but also impacting girls experiencing homelessness around the country.

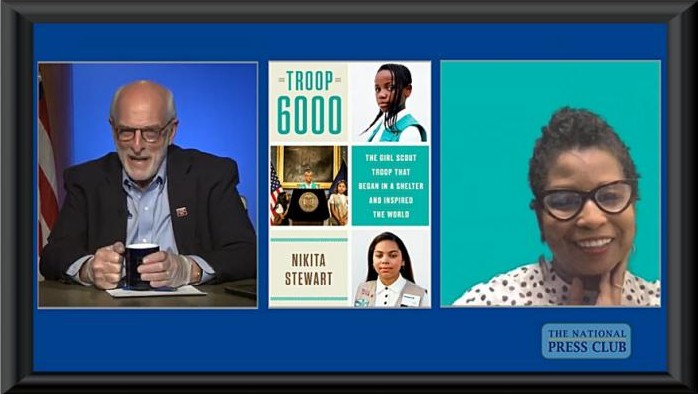

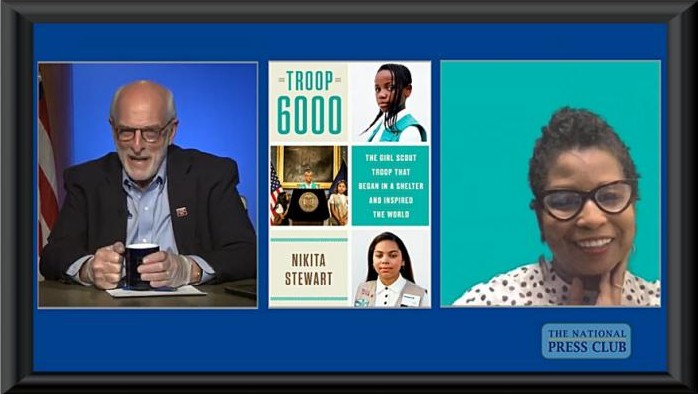

Stewart then spent a year researching her book "Troop 6000: The Girl Scout Troop that Began in a Shelter and Inspired the World." Deferring to the new reality of social distancing, National Press Club President Mike Freedman interviewed Stewart May 21 for an online book rap while she was at home and he was in the Club’s Broadcast Operations Center with a small staff.

Stewart said she wanted to break the stereotype of homelessness: the guy holding a piece of cardboard on the street. A large percentage of the homeless are families, she pointed out, who are often living with relatives in overcrowded situations. Girls Scouts, in particular, offer a surprising twist on homelessness. “You just don’t think of a Girl Scout being homeless,” Stewart said. “She’s the one selling cookies outside the supermarket.”

Troop 6000 was founded by Giselle Burgess, a mother of five who had been working at the Girl Scouts of America when she was evicted and entered the New York City shelter system. Living with her children at a Sleep Inn used as a shelter, she noticed that residents mostly kept to themselves, the children spending almost all of their time in a crowded budget hotel room. According to Stewart, Burgess asked herself, “Why can’t I start a troop in the shelter where I live?”

Barreling through several layers of red tape with the hotel, various city departments, and the Girl Scouts of America, Burgess finally won approval to start a troop and then had to convince the parents to let their daughters join. The troop started with eight girls, including Burgess’s three daughters, then rapidly expanded after Stewart’s article appeared.

Girl Scout troops now meet in 20 New York City shelters, and countless more have begun meeting in shelters around the country. Dues and other costs are subsidized. The Girl Scouts of Greater New York, for instance, received a $1.1 million grant from the city.

Stewart saw the impact of the 108-year-old organization on members of Troop 6000 who learned sisterhood, community, and civics, and had one day a week of fun, play, and joy. “Many homeless children are embarrassed and hide their lack of housing,” she said. “Now Troop 6000 is a badge of honor. 'I might not have housing, but I am resilient.'”