NPC in History: Jive, Jazz at Club helps break color barriers

Former National Press Club President Larry Lipman sent me an old ad he had come across:

Billie Holiday was an African American jazz soloist who had a seminal influence on jazz music and pop singing from the 1930s to the 1950s. Lipman wanted to know what year she appeared at the Club and was there anything more I could learn about the event. After all, when could you see a big-name entertainer for $1.10?

That sent me off on a quest that ended up teaching me something about the role the Club played in integrating entertainment in Washington.

Washington in the 1930s and 40s was a strictly segregated city, including in entertainment. Black and white musicians did not perform together, and black and white audiences did not sit together.

The story then moves – improbably – to the Turkish embassy on Sheradin Circle. In 1934, a new ambassador, Mehmet Ertegun, moved in with his two sons, Nesuhi 17, and Ahmet, 11. They immediately embraced American culture, especially jazz. They scoured record stores for the latest recordings.

“They arrive waiting and anxious and wanting to witness this music firsthand,” Anna Celenza, a Georgetown University music professor and jazz historian, was quoted as saying in an article by Mikaela Lefrak for WAMU.

They soon started going to the jazz clubs such as the Howard Theatre on U Street where they saw musicians like Duke Ellington, Joe Marsala and Jelly Roll Morton.

Ahmet and Nesuhi thought it was absurd that the audiences were either all black or all white and that musicians of different races rarely performed together, Lefrak wrote.

“You can’t imagine how segregated Washington was at that time,” Nesuhi told The Washington Post in 1979. “Blacks and whites couldn’t sit together in most places. So we put on concerts … Jazz was our weapon for social action.”

They convinced their father to allow them to invite musicians – both black and white – to come to the embassy for lunch and to jam. This caused some consternation in the neighborhood, especially from a Southern congressman neighbor who protested when he saw African Americans entering through the embassy’s front door. A photograph shows them all enjoying lunch around the embassy’s formal dining room table.

By 1942, the brothers decided to take this to the next level – finding a venue that would allow mixed audiences listening to mixed performers.

It wasn’t easy. The first concert was at the Jewish Community Center.

“The people at the Jewish Community Center did not know it was going to be integrated,” Maurice Jackson told Lefrak. “Blacks and whites just don’t go to things together. But by the time they’d done all the publicity, it was too late.”

And that brings us to the National Press Club.

At the time, the Club’s membership was segregated – and would be until 1955. But Ahmet and Nesuhi worked on the Club’s leadership until it relented to allow them to hold concerts in the auditorium – what we call the ballroom now.

Before the Club was remodeled in the 1980s, the ballroom had a stage on the far end so that the room could be set up theater-style for productions.

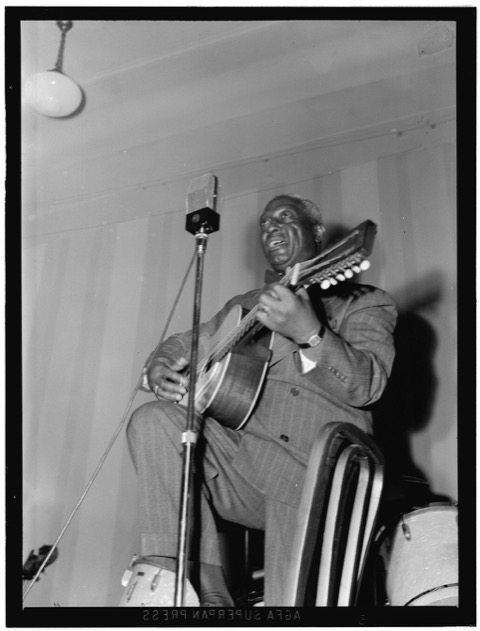

The first concert the brothers put on at the Club featured Lead Belly (often written Leadbelly), the performing name for Huddie William Ledbetter, a folk and blues singer, musician and songwriter, known for his strong vocals and virtuosity on the 12-string guitar.

Ahmet described to Jackson what happened this way:

“Leadbelly used to come to some of our open jazz sessions at the embassy, and he sang at the first concert at the National Press Club. When he peaked out from the wings back stage and saw the size of the crowd, he said ‘man, you gotta give me double the price, otherwise, I’m not going on.’ So, of course, we did – we gave him everything we could, and you know we certainly were not pretending to be experienced promoters, we were just doing it for the love of the music.”

And so, the Club was instrumental in breaking the color line for entertainment in Washington. The Ertegun brothers never went back to Turkey. Ahmet moved to Los Angeles and founded Atlantic Records. His brother joined him a few years later. At one time, Ahmet was chairman of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

But that still doesn’t answer Larry Lipman’s question.

Now that the Club could be a venue for mixed-race audiences, it attracted other performers.

A short item in the Nov. 1, 1943 Washington Post announced: “Billie Holiday, jazz collectors’ notion of everything a blues singer should be, will give out her own interpretations of some lowdown jive at the National Press Club auditorium next Monday night, Nov. 8.”

A later article called it “Washington’s first jazz concert in many months.” It was organized by “the Washington Workshop, a Government employees recreation group.”

Holiday was accompanied by Eddie Hayward, “whose trio also will dish up some jive for the Capital cats,” The Post said.

Now THAT would have been entertainment – all for $1.10.

This is another in a series provided by Club historian Gil Klein. Dig down anywhere in the Club’s 112-year history and you will find some kind of significant event in the history of the world, the nation, Washington, journalism and the Club itself. Many of them have been put together in a book, “Tales from the National Press Club,” which will be released by The History Press on April 27.