Mexican journalist’s 15-year asylum case exposes flaws in immigration system, free press advocates say

A Mexican journalist’s 15-year pursuit of asylum in the United States exposes systemic problems with the U.S. immigration system, legal experts and free press advocates said during a news conference Thursday at the National Press Club.

Emilio Gutiérrez Soto fled Chihuahua with his son and sought asylum in the U.S. in 2008 after receiving death threats following the publication of his stories about military corruption. His asylum case stalled before an unsympathetic immigration judge in El Paso, Texas. Since then, federal officials have detained him twice without evidence of a crime.

In September, Gutiérrez Soto finally won the case when a three-judge appeals court overruled the El Paso immigration judge. But the group of his supporters who ultimately won his freedom said the U.S. immigration needs sweeping changes as journalists flee persecution all over the world and thousands of immigrants are caught up in an opaque system.

“We’re at a conclusion, but we’re not at a point of celebration because all of the systems that made this possible to happen to Emilio are still in place,” said Lynette Clemetson, director of the Knight-Wallace Fellowship at the University of Michigan, which awarded Gutiérrez Soto the prestigious academic fellowship while he was still detained.

It was criticism of the U.S, immigration process that got Gutiérrez Soto into trouble. In 2017, as his case dragged on and his supporters sought more publicity for his plight, the National Press Club named him the 2017 John Aubuchon Press Freedom Award honoree. In his acceptance speech, he said the immigration system was broken.

A couple months later, immigration officials abruptly handcuffed him by during a routine meeting and drove him toward Mexico, despite a pending filing in court.

“I was in shock,” said Eduardo Beckett, an El Paso-based attorney who was with him at the time. “I’ve never had the situation where they’re deporting someone in front of my face.”

After frantic phone calls to the immigration court, Gutiérrez Soto was returned, but thrown into arbitrary detention. He was eventually released. Emails provided in response to Freedom of Information Act requests filed by Kathy Kiely, a journalism professor at the University of Missouri, indicated criticisms in his speech were a factor.

Empowering journalists is good U.S. immigration policy, Kiely said. If the U.S. closes the door to asylum for journalists facing persecution, corruption will fester in their home countries and cause even more people to flee to the U.S. border.

The situation in other countries has even created new problems for academic fellowships such as those at Knight-Wallace and Missouri, which have hosted reporters from other countries with the hope that they will return to their homes and speak truth to power, she said.

“The problem is that those emerging democracies are now backsliding,” Kiely said. “And If we send people back, we are sending them back to jail or worse.”

The case revealed the need for a legal task force of First Amendment experts to represent asylum seekers and others to simply observe courtroom practices, said Penny Venetis, a law professor at Rutgers University who served as an attorney for Gutiérrez Soto.

“You need people who know these issues and who understand the process and who are sympathetic to people who are being threatened with assassination for practicing their craft,” Venetis said. “If it can happen to Emilio, it can happen to anybody.”

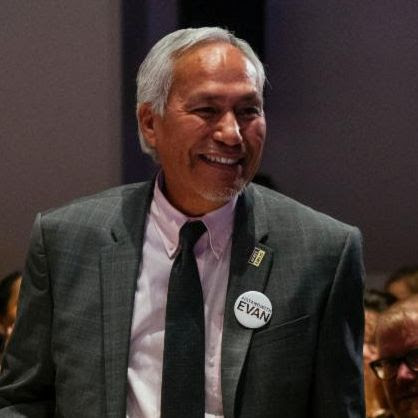

Gutiérrez Soto, speaking Spanish and sporting a “Free Emilio” pin, thanked everyone who helped him – but he was careful with his words for fear he could be thrown back in jail.

“These 15 years have been quite difficult,” he said, through a translator. “I feel profoundly grateful for everyone here.”